Contextual Inquiry was the user research method chosen because it gives realistic data as it uses a natural setting to gather behavioural insights around the use of a product, in this case, MyFitnessPal.

A master-apprentice technique will be employed (Beyer and Holtzblatt, 1998). By design, the context inquiry makes it possible to reveal tacit knowledge. Other relevant aspects are that the information that emerges tends to be accurate and it produces highly detailed data. The goal was to observe commonly used features: adding food to their diary, monitoring progress, managing calorie intake and updating goals. The contextual inquiry was conducted in a place where users typically interact with the product. The results will be used to define requirements.

Six MyFitnessPal’s users, matching the proto-persona defined in the questionnaires, were sourced.

Along with the contextual inquiry, a semi-structured interview (Annex 4) was performed to gather information necessary to triangulate the information from the questionnaires. Before the contextual inquiry, users were informed about the project, what was the goal of that exercise and were asked to sign a consent form (Annex 5).

Figure 1. One of the contextual inquiries performed with a MyFitnessPal’s user.

The videos, audios and notes from the contextual inquiries can be observed in Annex 6.

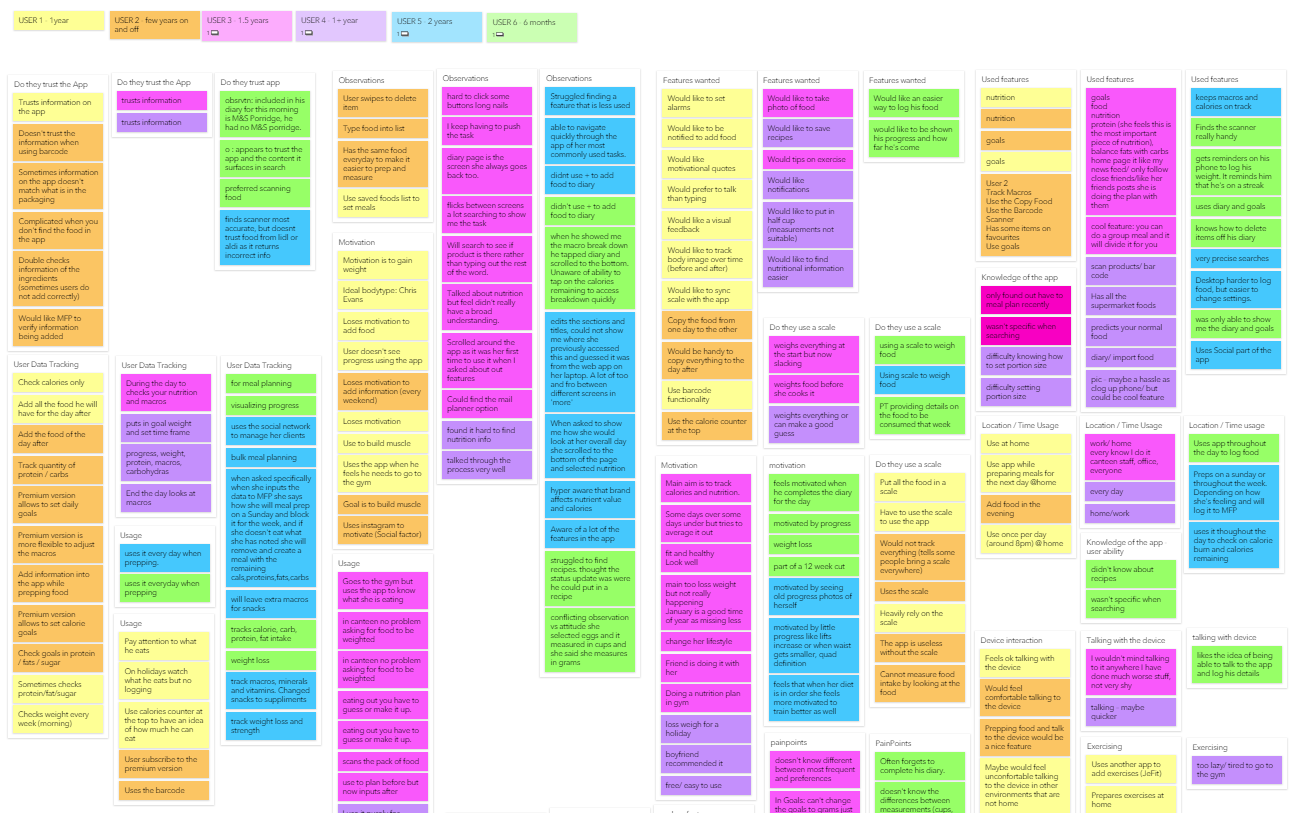

The main points were added in virtual Post-Its on an online tool called Boardthing (Fig. 2).

Afterwards, the Post-Its were grouped by themes (Annex 7), and the topics that raised were discussed:

- Trust issues with data in MyFitnessPal

- Observations of use

- Desired Features

- Used Features

- Location of use & Time of use

- The information being tracked

- Motivations behind usage

- The use of scale to measure food weight

- User abilities

- Useless Features

- Pain Points

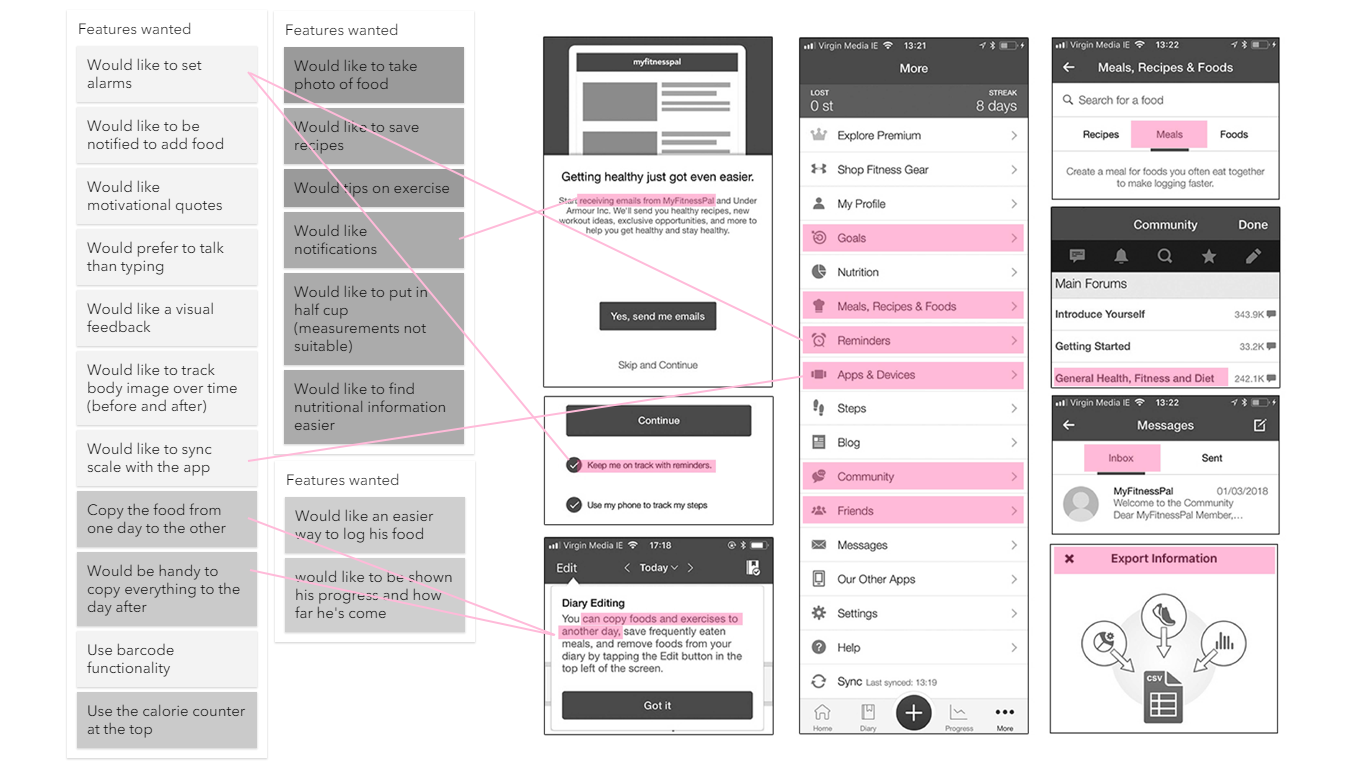

No major issue surfaced during the Contextual Inquiries – users were satisfied with the current solution. Despite the attitude of the users when reviewing the contextual inquiry, all users struggled to locate and demonstrate features in the app. Another point was that users mentioned desired features that they would like to have within MyFitnessPal but these features already existed in the app (Fig. 3). Over a period of time, long time users were demonstrating the same behaviour as novice users.

Another example is that users responded to the questionnaire that they have more long-term goals than short-term goals but the contextual inquiry revealed that users have more short-term goals – often initiated when a life or social event appear on the horizon.

References

Beyer, H. & Holtzblatt, K. (1998). Contextual Design: Defining Customer-Centered Systems. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.